Words by Zachary Masone

In 2006, a teenage Taylor Swift opened her debut single “Tim McGraw” with the line, “He said the way my blue eyes shined put those Georgia stars to shame that night / I said that’s a lie.” Astute yet un-complex, Swift proved from a very early age that she could synthesize her experiences into bulletproof country-pop records that could be both universally applicable and deeply personal. In the two decades that have followed, that young artist has blossomed into the most famous person in the world. Her latest tour, The Eras Tour, was attended by over 10 million people, spanned over 5 continents and 51 cities, and grossed over $2 billion, becoming the highest grossing tour of all time. Her albums continuously sell millions of copies (including the re-recorded versions of her previously released works), with 2022’s Midnights being certified 7x platinum and 2024’s The Tortured Poets Department being certified 8x platinum. She has won Album of the Year at the Grammys four times, the most for any artist, and is the only artist to occupy the entire top 10 of the Billboard Hot 100 at the same time (and for the cherry on top, she’s done it twice). She truly has developed into an unstoppable force, an entire genre of music in and of itself. With the Eras Tour over, though, Swift has found herself in an interesting spot. Where does an artist who has achieved everything go from there?

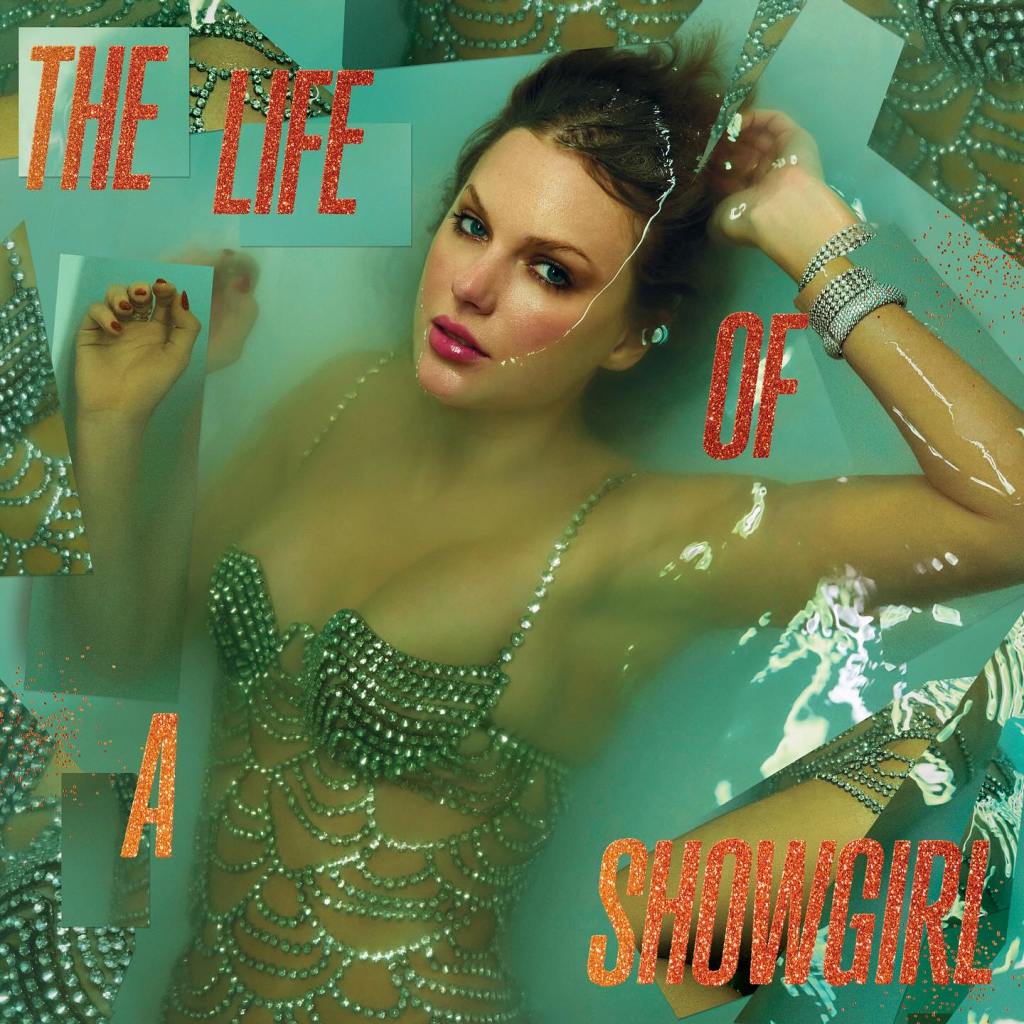

Her latest album, The Life of a Showgirl, is her most recent creative output in her prolific release strategy of the past five years or so. You can count on Swift to unleash an album, either a re-recording of an old album or an album full of original tracks, at least once a year. She has groomed the public to expect and yearn for, wallets open, a new project. With her old works under her belt (bought back from Shamrock Capital in May 2025 for an undisclosed amount), it seems as if the re-recording project has come to a halt. The next thing to do was to release a brand new studio album. For Swift, the more is unquestionably merrier. Midnights and The Tortured Poets Department came in swift succession in between Fearless (Taylor’s Version), Red (Taylor’s Version), Speak Now (Taylor’s Version), and 1989 (Taylor’s Version), with all six of these albums coming out between the years 2021 and 2024 (excluding 2020’s folklore and evermore). In addition to her hyper release strategy, Swift’s tracklists have also ballooned to keep up with tactful streaming schemes (the more tracks, the more streams). Red (Taylor’s Version) had 30 songs, Midnights (The Til Dawn Edition) had 23 songs, and The Tortured Poets Department: The Anthology had 31 songs respectively. This strategy of copious and bloated output, maximizing her exposure with the public, has proved extremely profitable for Swift. She continually breaks streaming and sales records, with The Tortured Poets Department moving over 2.6 million units in its first week (the second highest sales week of an album of all time, only behind Adele’s monumental 25, which sold 3.38 million units in its first week). She lives in the stratosphere of artists like Adele, Michael Jackson, and The Beatles in terms of massive commercial performance. But, I think what has become abundantly clear is that these other artists have something that Swift seemingly lacks the further and further we move forward – the artistry to back up these sales. Or, perhaps, the mentality that the art, before all else, should come before the revenue.

To put it plainly, The Life of a Showgirl is not very good, which is becoming an increasingly unsurprising reaction to Swift’s releases, but nevertheless, extremely disappointing. The album was sold as a combination of folklore-level storytelling and lyricism mixed with the infectious melodies and pop bangers of 1989. What we got was neither of those things, much less them combined. The Life of a Showgirl is lifeless and stale, dated upon release, and complete with some of the year’s worst writing coming from this generation’s so-called best songwriter.

The album starts out well, however, and there is a glimmer of what the record could have been from the first four tracks (which are the best on the album). The opening track, “The Fate of Ophelia,” is a top-drawer Taylor Swift song, and the accompanying music video is the best one Swift has ever self-directed. It’s groovy and bright, with the chorus and post-chorus melodies becoming instant earworms. “The Fate of Ophelia” leads into “Elizabeth Taylor” and “Opalite,” which are innocuous and catchy single-ready tracks. There is some lush orchestration on “Elizabeth Taylor” that calls to mind the opening of “Everything is romantic” by Charli XCX, and Opalite has a fun 1960s-esque production that suits Swift’s voice. Already though, the Showgirl aesthetic of the album cover and photoshoot, which sees Swift sparkling in glitzy Vegas-style costumes adorned with ostrich feathers and diamonds, is a mismatch to both the sonics and lyrics of the album. It’s much less about the life of a showgirl, and rather the life of a girl in love, as already the main focus of the album is her newfound relationship with Travis Kelce. “Father Figure” is the last recommendable track on the album. It samples George Michael’s classic song by the same name, which Swift puts to good use on the chorus. While the mob-boss lyricism is perhaps overdone, the melody alone, again, makes this song worthy of a listen. It’s perhaps a bit startling, however, that one of the most notable melodies on an album supposedly crafted with melodic mathematics in mind does not even belong to Swift or her band of producers.

After “Father Figure,” however, the album takes a complete and utter nosedive, sinking into baffling territory that I’ve yet to fully understand. Swift emphasized prior to the album’s release that she was putting together a team of creatives at their artistic peaks. Her sonic storytelling and songwriting were honed on indie-folk classics folklore and evermore, while her producers, Max Martin and Shellback, created some of this century’s best pop songs, including The Weeknd’s “Blinding Lights” and Ariana Grande’s “we can’t be friends (wait for your love)” (this does not include Swift’s masterworks, “Blank Space” and “Style”). It seemed like a recipe for success, a sure-fire sales and critical darling. While the first four tracks were nothing remarkable or instantly iconic, they were also nothing offensive. The same can’t be said for the rest of the album.

I’m not sure what the most egregious thing on the record even is. It’s possibly the fact that “Eldest Daughter” is track five, a notoriously prized spot on any Swift tracklist, known to contain Swift’s most vulnerable and emotional songs on her albums. Previous track fives include “All Too Well,” “Dear John,” and “You’re On Your Own, Kid,” to put into perspective the caliber of songwriting and personal perspective expected from this track placement. Instead, Swift warbles over a lazy piano, “Every eldest daughter was the first lamb to the slaughter / So we all dressed up as wolves and we looked fire / But I’m not a bad bitch, and this isn’t savage.” It’s millennial Internet-buzzwords with all the emotional resonance of a slogan on a tote bag. It’s garbled TikTok slang paraded as satirical social commentary (And this is the same person who wrote, “And you call me up again just to break me like a promise / So casually cruel in the name of being honest / I’m a crumpled up piece of paper lying here” over a decade ago).

Or maybe it’s “Wood.” There’s an obvious metaphor here that was clocked from the moment the tracklist was revealed, but I thought was all too obvious for the level of songwriting expected of Swift. But no, we actually do receive a song about Kelce’s “wood,” so to speak. And it’s not as if Swift has never written a song about sex or being sexual; that’s not the issue. Songs like “False God” or “Dress” are filled with innuendos (“The altar is my hips / Even if it’s a false god / We’d still worship this love”), but there’s a level of tastefulness and sincerity that makes these songs work. Instead, on “Wood,” Swift puts on her Sabrina Carpenter wig and tries her best to play up the deeply awkward sexual humor, dialing everything up to a ten except for the quality of the song itself. Over a Jackson 5 sample (why?) that sounds like “I Want You Back” mixed with the back half of the Trolls soundtrack, Swift sings about redwood trees, magic wands, and “New Heights of manhood,” simultaneously shouting out Kelce’s football podcast and his penis in the span of four mere words. It’s truly one of the worst songs she has ever released.

Or, possibly, it’s “CANCELLED!,” which is spelled in all capital letters and complete with an exclamation point. No Swift album is complete without a song about being cancelled (“Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me?” from The Tortured Poets Department, “mad woman” from folklore, and “Look What You Made Me Do” from reputation), which is obviously not a very universal experience, but Swift is one of the most famous people in the world. Cancellation is a part of the culture, and Swift has a right to contemplate the implications of fame. Fine. The problem with the song (besides the fact that it sounds like it came straight out of a scene from Netflix’s The Hunting Wives) are the insinuations one can glean from what Swift is actually saying. She sings on the chorus, “Good thing I like my friends cancelled / I like ‘em cloaked in Gucci and in scandal.” When she surrounds herself with people like Brittany Mahomes, who are vocal Trump supporters, or when the very public trials of Diddy are consuming popular attention, it truly calls into question what Swift means when she sings, “Welcome to my underworld / Where it gets quite dark / At least you know exactly who your friends are.” If she is exaggerating, then now isn’t exactly the cultural moment to release an anthem for people who feel like they’ve been cancelled, and if she isn’t exaggerating, then just exactly who is she choosing to surround herself with and what have they actually done?

Beyond the aforementioned reasons, none of these songs even play into the theme of the showgirl whatsoever. It seems as if Swift had a vague concept of what she wanted the album to be, came up with the title and the photoshoot, but didn’t have nearly enough time to actually execute that vision. Nothing about the lyrics or the production have anything to do with showgirls or what you might expect an album called The Life of a Showgirl to sound like. There are no Burlesque references, no clear theatrical influences, no real drama or glamour. Swift’s recent policy of not releasing any singles before the album drops worked against her here, at least critically, as it allowed an idea of what the album should sound like proliferate to the point where nothing Swift could release would match the standard the fans had made up. But, can you blame them?

When Swift comes off the heels of the biggest tour of all time, announcing an album that seems, at least based on the title and photoshoot, deeply entwined with being the star of that experience, it’s not wrong to expect musings on what headlining the Eras Tour truly meant to Swift. There was no real behind the scenes documentary, no social media insight, even as her relationships with Matty Healy and Joe Alwyn fell apart and her new relationship with Kelce bloomed, all on the tour itself. How did she deal with the pressure of millions of fans expecting her to be perfect? How did she feel knowing that her tour was generating revenue like no tour before it ever had, boosting the economies of every city it passed through and triggering the conversation on the dismantling of the Ticketmaster monopoly? How did she continue to perform her back catalog knowing that she had a very public battle to regain the rights to her masters, only to continue to re-record them on the road, and then eventually buy the master recordings back? For the answers to these questions, The Life of the Showgirl reveals nothing.

And that, perhaps, is the greatest misfortune of all. There is so much potential here. An album with this concept, put out by the biggest artist in the world in their prime on the heels of the biggest tour of all time, has so much promise. And we know that Swift can deliver – she has before on albums like Fearless, 1989, and folklore. So what happened?

This plenteous output strategy employed by Swift has generated great commercial success, but has also caused her creative success to falter. When output is the goal, there is little time to think, ponder, and most importantly, edit. Her prior albums before folklore all took at least two years to be released after her last album, and there is a stark difference in quality between her previous works and her run from Midnights in 2022 to the present day. While it can be freeing for an artist to have more creative control, which Swift gained after leaving Big Machine Records in late 2018, it can simultaneously hinder them. It feels like Swift was in the driver’s seat the entire time while creating this record, with Max Martin and Shellback only assisting as best as they could to execute the vision that she had surmised. But, this vision was clunky and deeply flawed. What is Showgirl about getting “wet” at Charli XCX dissing you? What is Showgirl about wishing you kissed a long lost friend before he passed? What is Showgirl about your man calling you “Honey” or “Sweetheart”? Nothing. Swift needs time. The problem wasn’t the long, sprawling tracklists or the Jack Antonoff production, clearly, for more issues seem to have cropped up on this record than have been resolved. It is Swift herself who seems fundamentally out of touch with the work that she is creating. It’s not enough to churn out an album every year in hopes that your fans will purchase and stream it enough to break whatever records you don’t currently hold. There is something missing. The Life of a Showgirl is the year’s most disappointing record, the lovechild of power and control without any introspection. It is complacent, tacky, and most damning of all, boring. It’s the deflated balloons hanging on at the end of the party, the stray pieces of confetti blowing in the wind on the Vegas strip the morning after. It lacks both purpose and cohesion, momentum and vision. I beg Swift to close these dancehalls forever, hang up the costumes, and take some time. Please, fall back into the shadows and away from the spotlight, just long enough so that you remember why you ever walked into it in the first place. The show must not go on.